The exhibition A KIND OF LANGUAGE: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema, curated by Melissa Harris, is currently on display (30 Genuary 2025 to 8 September 2025) at Osservatorio Fondazione Prada in Milan, Italy. It is located within the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II and accessible via the M1 and M3 underground lines at the Duomo stop.

Photo: Piercarlo Quecchia – DSL Studio / @piercarloquecchia – @dsl__studio Courtesy: Fondazione Prada

My journey to the exhibition, despite my navigational challenges, doors, elevators, and even the Prada handbags displayed in the storefront windows, proved a momentary distraction: “Feeling Buster Keaton, close to where I should go!?…” had a happy ending.

I can assure you though that the Osservatorio Fondazione Prada is easily located to find for those with better orientation than myself. The reception staff are invaluable, and the exhibition is a thoroughly rewarding experience from beginning to end. Obsessed cinema professionals and enthusiasts, like myself, will find it particularly captivating and may find it difficult to leave; you just want to stay a little bit longer and see everything again. So, let’s delve in storyboards!

Early in my filmmaking studies, to better grasp the storyboard’s function, I conceptualized it as a “communication map”, a tool to navigate and understand the complex creative process of making a movie.

And this is why!

The storyboard is created in the pre-production phase and is a crucial tool for film directors, enabling them to narrate their story visually and facilitate effective communication before filming and during all operational phases between the crew that builds the film, from the DOP to the actors in the production process to the post-production phase of editing. Essentially, a storyboard is a sequential visual representation of the film, typically rendered as a series of drawings on paper. This instrument aids in determining key elements such as space and time orientation (location and time of the day), frame composition, camera angles, and lighting direction.

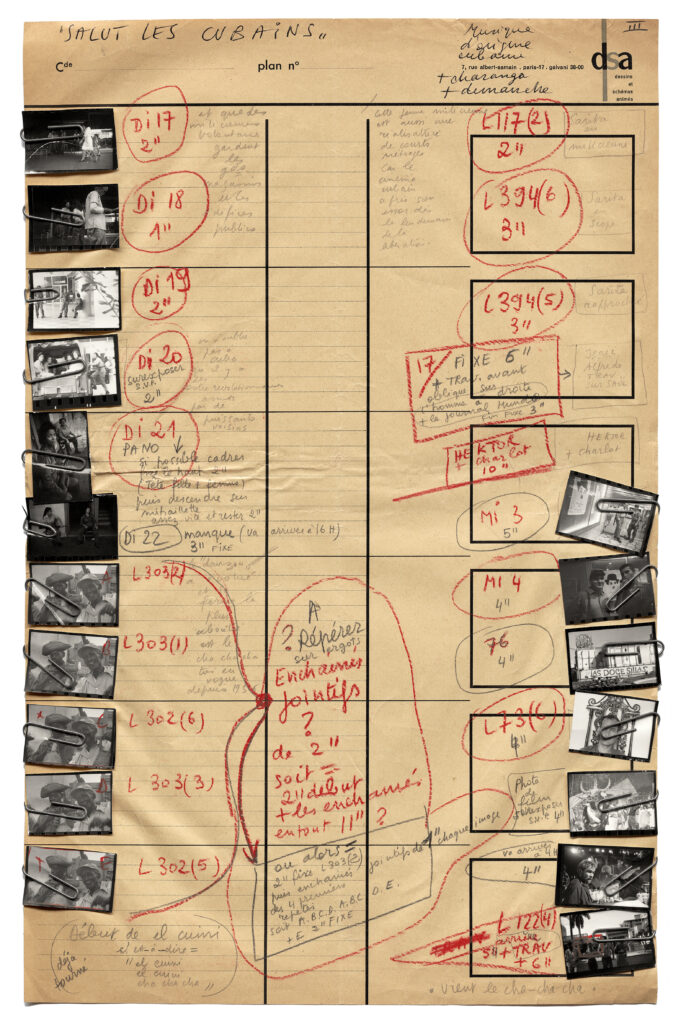

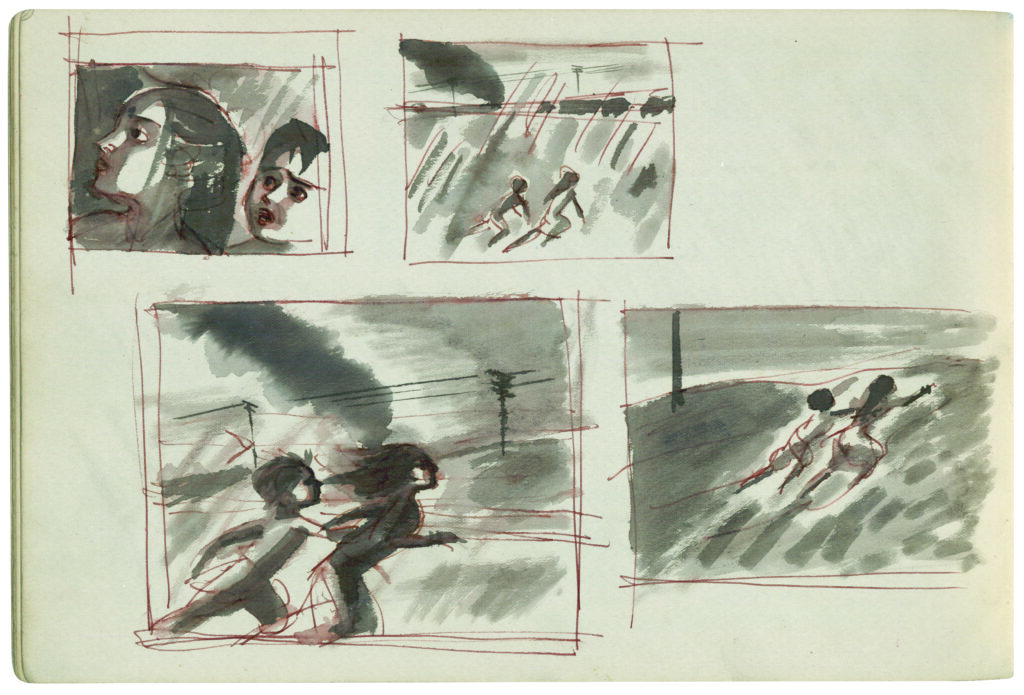

It can also be a “map” to orient character movements and relationships between them. While this provides a foundational understanding of the storyboard’s purpose, its application and its creation vary significantly. From the meticulously detailed storyboards of Alfred Hitchcock, like in the film Rebecca (1940), which meticulously planned every shot, to the more “minimalist” sketches employed by Pier Paolo Pasolini as in Mamma Roma (1962) as his main interest was the psychological backgrounds of the heroes, which focused on essentials, storyboards adjust to diverse directorial styles. My personal preference leans towards the photographic storyboard, a technique exemplified in the works of Agnès Varda, like in Salut les Cubains (1964). This approach utilizes a sequence of photographic frames, often featuring model actors or even the film’s eventual cast, to articulate the narrative visually. The traditional storyboard typically comprises small-scale drawings accompanied by short or long verbal descriptions. However, contemporary adaptations demonstrate a broader artistic range, incorporating techniques such as collages and animated video storyboards, as seen in films like The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), with storyboard images by Jay Clarke and animation editing by Edward Bursch and the director of the film Wes Anderson. Notably, storyboards are also integral to animation, with Walt Disney Productions playing a pivotal role in formalizing their use in filmmaking.

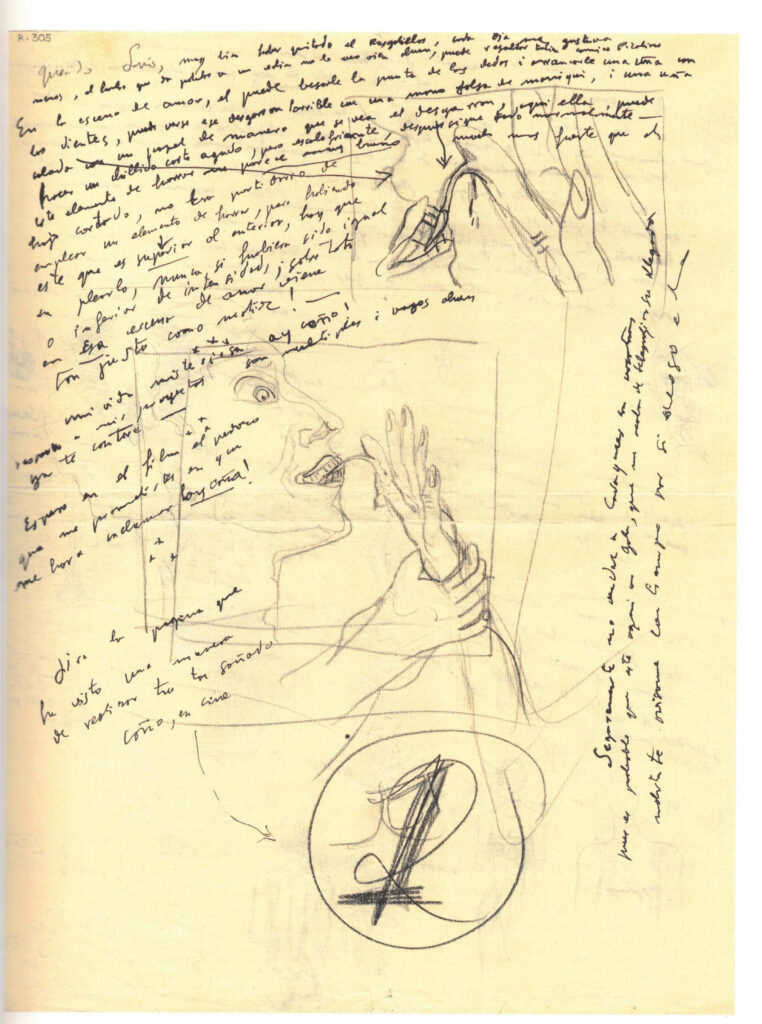

Though specialized university programs exist for aspiring storyboard artists, the creation of storyboards often falls to the director, underscoring its essential role in their creative process. Sometimes, their storyboards have identities and style characteristics like a piece of art that you can identify who is behind the drawing. A unique example is Federico Fellini and his sketches for the film Amarcord (1973) and, of course, the versatile master of Swedish cinema and performative arts, with the unique perception of lights and actor’s positioning in the frames Ingmar Bergman with his shooting scripts and work diaries like in the film Persona (1966). Usually, the general audience knows who is the director of a film is, especially in Europe, which is the main axis in the process of filmmaking. If we are in the USA, it is common enough to know the producer who is the central figure in the films, too. But it is rare to know who are the rest of the cinematographic crew, the DOP, editor, costumist, music composer, etc. Imagine the storyboard maker! As we saw previously, sometimes they don’t even exist in a film preparation. So, two questions that arise are: “Who are (those) storyboard makers? And, of course, what is the role of the storyboard in the process of moving image narration?” Answers that the exhibition provides.

(The film examples referenced in the above introduction were deliberately chosen to align with those featured in the exhibition and with the scope to be educative and function as a short introduction on what a storyboard is).

About the exhibition

A KIND OF LANGUAGE: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema at Osservatorio Fondazione Prada offers a focused exploration of storyboards, revealing their pivotal role in the filmmaking process from the late 1920s to the present day. Through a meticulously curated selection of storyboards, drawings, sketches, notations, and photographs, the exhibition provides a media archaeology perspective on the evolution of cinema, highlighting the inherent effort, complexity, and creative ingenuity involved in making moving pictures. The staging, designed by Andrea Faraguna of Berlin-based Sub Architecture Firm, employs a minimalist yet multifaceted approach. Storyboards are displayed on furniture reminiscent of drawing tables, maintaining the sequential structure of cinematic film and creating a seamless visual connection with the external cityscape visible through the Osservatorio’s windows. This design effectively reinterprets the working environment of storyboard artists, transforming it into a compelling spatial experience that underscores the exhibition’s thematic focus.

What makes this exhibition unique:

This exhibition distinguishes itself by focusing on the storyboard and its integral role in the filmmaking process, and which rarely can be seen standing by them own as unique works (as a kind of language), offering visitors the opportunity to discover the contributions of notable professional storyboard artists such as Pablo Buratti, Saul Bass, Jay Clarke, Gabriel Handman, Ron Cobb, Satyajit Ray, and David Byrne.

It also showcases artists who have engaged in script visualization, such as Salvador Dalí in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), and instances where script and visualization are intricately interwoven, as exemplified by Jean-Luc Godard‘s script-collage manuscript for Le Livre d’image (2018).

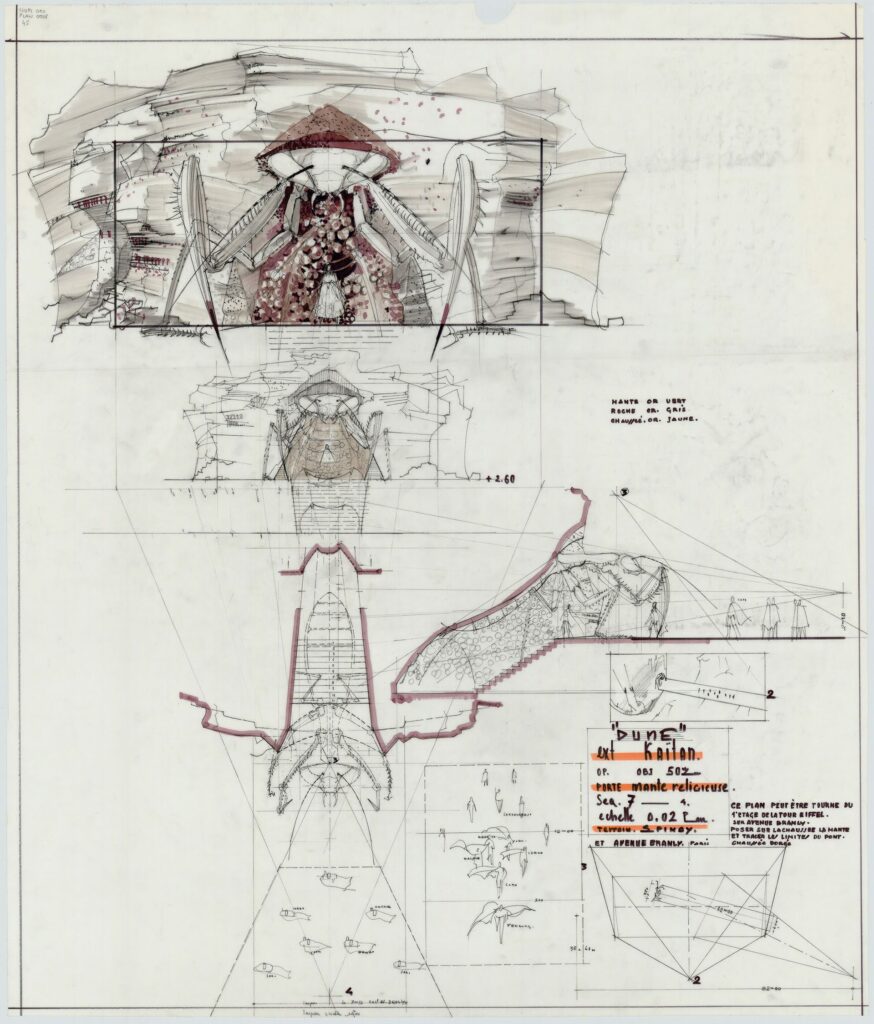

Beyond storyboards, the exhibition effectively integrates sound, video, and interactive table surfaces, creating a comprehensive cinematic atmosphere. The subtle inclusion of the shower sound accompanying Saul Bass‘s storyboards for Alfred Hitchcock‘s Psycho (1960) is a particularly insightful touch. The display of Alejandro Jodorowsky‘s unproduced Dune (1973/77) storyboards is a truly particular moment as many films remain on paper without ever having been produced, and we seldom know about them. Furthermore, the collaboration between choreographer Merce Cunningham and Charles Atlas, presenting a storyboard for choreography alongside camera movement notes, for the Torse (1976), which is a film of a choreography, offers a fascinating glimpse into interdisciplinary creative processes. The inclusion of television series storyboards, such as Pablo Buratti‘s work for Álex de la Iglesia‘s 30 Coins, added another layer of depth in exploring the possibilities that provided the expansion of moving images. A particularly comforting moment is encountering Hayao Miyazaki‘s storyboard blocks for The Boy and the Heron (2023), which evoked a strong desire for me to engage with the creative process by sketching the next scene.

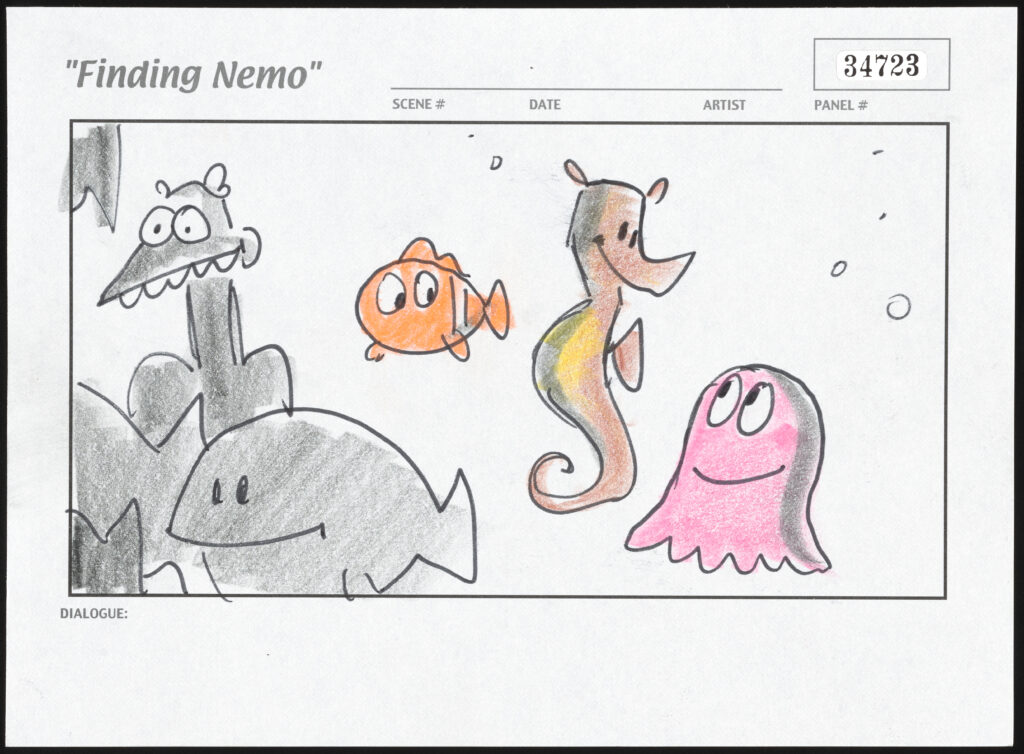

A must-visit exhibition for cinema professionals, aspiring cinemographers, art-interested individuals, and everyone else, especially those who choose to go to the cinema on a Saturday night. Or, simply take your kids and let them explore what was behind the making of the film Finding Nemo (2003), directed by Andrew Stanton.

Fondazione Prada

Fondazione Prada, established in 1993 by Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli, is a cultural institution dedicated to fostering a deeper understanding of the world through art and research. It achieves this by promoting diverse cultural activities, including exhibitions, research projects, conferences, film events, and educational programs across its venues in Milan, Venice, Shanghai, and Tokyo. Collaborating with a global network of artists, curators, scientists, and intellectuals, the foundation explores various disciplines, such as art, architecture, cinema, philosophy, and neuroscience, aiming to stimulate innovative perspectives and investigate the impact of artistic and intellectual research on human life, ultimately driving cultural innovation and dialogue.

As we talk about cinema I considere really significant to add that in the steering committee is member a master of contemporary cinema with a multifunctional artistic talent Alejandro González Iñárritu with landmark films in his career like Amore Peros (2000), 21 Grams (2003), Birdman (2014) and the short film experience Carne y Arena (2017).

To learn more about the projects of Fondazione Prada Milano, and plan your visit go to their website Fondazione Prada – Mostre e progetti in cors

If you feeling as taking an even deeper knowldege, a book about the exhibition is available in italian and english language.

Thank you for reading, enjoy your visit at A Kind of Language!

► View SourcesSources

Fondazione Prada – Mostre e progetti in corso visited 06/03/2025